Curmudgeon Castle was every bit as dim and damp as Basil remembered. He followed Fergus down the ill-lit hallways and found his mind returning to that day, years ago, when the Conclave had asked him to visit a few prospective acolytes. Fergus had been one such—a promising young lad eager to be trained and recognized by the ruling body of wizardry. As welcoming as the parents of the young Fergus Curmudgeon had been, and as much effort as they had put into making a good impression, it hadn’t changed the reality that a castle’s halls are poorly lit, and more than a little cave-like. Basil realized how much he missed his own cozy hill-top home.

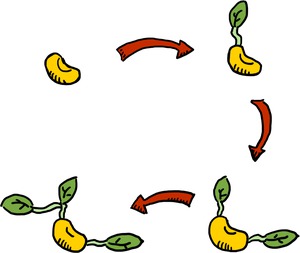

A promising young lad eager to be trained…

He suddenly had a vague memory of that bespectacled lad of years ago with a lanky, dark-haired younger brother—a mischievous troublemaker, as he recalled. It left him feeling off-kilter to realize that his manservant of several years was apparently that same rascally boy, a prodigal son who was now sitting in a dark cell in the dungeon of his boyhood home.

“So, ah,” said Basil, breaking the humid silence. He stroked his great mustaches. “Fergus, may I ask what, exactly, Fabian did to deserve a—ah—‘basement suite’ on his homecoming?”

Fergus grunted. “No.” Gruffly. He walked a few more paces before adding, “And no questions. We’ll talk when we reach the drawing room.”

Basil sighed. There was no doubt that Fabian was an agitator—it’s how he’d ended up serving Basil in the first place. But the wizard couldn’t help him if he didn’t know what he’d done! Why did the man have to be so stubbornly secretive about his past? And why had Basil never pushed for more information in the first place? He cursed his complacency, and vowed he’d weasel every last secret out of his manservant at the very next opportunity.

The silence was oppressive, and Basil cast about for something else to talk about. Amid the dull gray of the flagstones that surrounded them on all sides, Fergus' Scottish attire was remarkably vibrant. His colorful Tam o' Shanter, in particular, seemed out of place. Yet Fergus didn’t speak with any kind of detectable brogue, and Basil couldn’t recall seeing anything Scottish when he’d visited years ago.

“You wear a kilt well,” Basil said carefully. “I didn’t realize your family was Scottish. Both parents?”

Fergus grunted again. “Neither,” he said. After a brief hesitation, he added, “I just wear it for the bagpipes.”

Basil raised a curious eyebrow and made to speak, but Fergus cut him off. “And no questions,” he said, more firmly, eying Basil. “Or you’ll sleep outside tonight.”

Basil closed his mouth and tugged on his mustache. Just once. And definitely not out of annoyance. Wizards don’t get annoyed.

A long hall where small windows let in meager light…

They passed through a long hall where small windows, high up on one side, finally let in some meager sunlight. Basil saw various statuary here, in a variety of sizes, and numerous paintings and tapestries. He looked closely at them as they passed, and while they were very masterfully executed, he decided that there was something…odd…about them.

One statue depicted a man seated on a milking stool, a pail in front of him, his hands raised as if milking some invisible cow. A painting next to it showed a beautiful green pasture, with rustic wooden fencing and small birds flitting overhead, but the pasture itself was empty. Some kind of diorama portrayed a small child reaching through a wooden fence, as if to pet something that wasn’t there.

Basil shivered as he considered the strange gallery. He opened his mouth to ask his host about them…and then thought better of it. He had a feeling that Fergus did not make idle threats, and he had no desire to forfeit the night’s sleeping arrangements.

They continued in silence for several more minutes before finally arriving at some modest wooden doors. Fergus sighed. “Here we are,” he said, as he pulled the doors open and ushered Basil inside. “The drawing room.”

Basil’s first impression was of a room carpeted in crumpled sheets of paper. Easels sprouted like awkward flowers at seemingly random intervals, and tottering piles of books suggested where tables and chairs might be located. Bookshelves lined the walls, but were mostly empty—Basil supposed the entire library was to be found in the scattered stacks that swayed like the stalks of some lexical flora.

Fergus shuffled into the room, kicking papers out of the way, boldly forging a path through the bookish jungle. He reached a pile of folios and loose papers and carefully moved them aside, revealing a chair, which he then made a token attempt at dusting before inviting Basil to sit.

Thoroughly astonished, Basil sat.

Fergus moved another pile of books to reveal a chair for himself. “Sorry,” he said gruffly as he seated himself. “The help can’t seem to keep on top of the drawing room, lately.”

It was then that Basil noticed that the papers scattered across the floor and positioned on the easels weren’t blank. Each was host to a rudimentary sketch of some four-legged creature, maybe a dog of some kind. Or a pig. Perhaps a cow? Basil really couldn’t tell. He wondered if there was a children’s nursery in the castle that periodically made the drawing room their—ah—“drawing” room.

A dog of some kind. Or a pig. Perhaps a cow?

Fergus fidgeted in his dusty plush chair, tapping the armrests nervously and glancing all around the room. Basil waited, as still as he could manage, but finally decided that it must be safe to ask questions now. He was pretty sure that the prohibition had only been until they reached the drawing room.

He cleared his throat carefully and gestured to the paper all around them. “Ah, so, these pictures—”

Fergus grunted and waved dismissively, still avoiding eye contact. He fidgeted a moment more, and then suddenly scooted to the very edge of his seat and pierced Basil with a glare.

“Why,” Fergus asked intensely, “have you taken my brother, of all people, under your wing?”

Basil leaned back, as if slapped by the intensity of Fergus' scowl. “I—”

“That scoundrel!” Fergus spat. “That blackguard! That he should even dare to return after the mess he made of things…” He shook his head at the floor before spearing Basil with another violent glare. “I never did figure out where he put my best thesaurus. But that’s not important now. I must know what your relationship is with him. How is it that he should be in your company, a wizard of the Conclave?”

Basil paused, stroking his mustaches with one hand and tapping the armrest of his chair with the other. He considered Fergus carefully. “He…is my manservant,” Basil said, finally.

Fergus waved his hand impatiently. “Yes, yes, I assumed as much, given that you said you’d be arriving with your servant, but…really? How could you have taken the son of a noble house as your manservant? That seems incredibly bold, even for a wizard.” His eyes flashed.

Basil waved a hand, as if in defense. “I had no idea he was your brother, Fergus! He never told me!”

“But you’d met him! Years ago, when you evaluated me.”

Basil nodded. “Well, yes, I’d met him, but he was just a boy then. You both were. I travelled a lot in those days—I met a lot of people. I would probably never have even recognized you, if I hadn’t been looking for you.”

Fergus nodded. “I suppose, but still…did he never tell you who he was?”

Basil shook his head. “Never. Just his given name. I saved his life a few years ago, and he entered my service after that.”

Fergus pursed his lips. “I just can’t imagine that boy taking orders from anyone. He was certainly hopeless enough when he lived here.”

Basil considered Fergus' words. “Well, yes, there is that. He’s flippant enough for an alley of clowns. But he’s taken his obligation to me very seriously. Barring the occasional bit of back-talk, he’s been very reliable. And the truth is,” Basil lowered his voice and leaned in confidentially, “the man’s a genius with a squeegee.”

A horrified expression fell across Fergus' face. He pursed his lips and shook his head abruptly. “I—no. You say you saved his life? When was this?”

Basil considered. “Three years ago? Four? Fabian would know. He’s much better at keeping track of things like that.”

Fergus squinted and muttered under his breath, counting on his fingers. “Four…five…yes, yes. That fits, but…” He focused on Basil again, and shook a finger at him for good measure. “The Conclave would be in fits if it found out you took a nobleman as a servant!” He hesitated a moment. “You even armed him with a squeegee!”

Basil shook his head and set his mustaches wagging. “Fergus, I told you! I had no idea! I honestly didn’t know, and he made no objection… And, actually, he kind of armed himself with that squeegee. Funny story, that…but…” He considered the look on Fergus' face. “Maybe now’s not the time…”

Fergus raised an eyebrow and considered Basil suspiciously, but sat back in his chair and said nothing.

Basil cast about the room, looking for a new subject of conversation. Something safer. For the first time, he noticed someone sitting behind one of the easels set up in the corner of the room. A man was partially hidden behind it, scribbling madly on a piece of paper. Basil watched as he crumpled up his current sheet and threw it to the ground, cursing quietly, before grabbing a fresh sheet and scribbling again.

Basil pointed to the man. “I say, Fergus, I had no idea someone was using this room. Are we bothering him?”

Fergus glanced up in surprise and looked where Basil indicated. He immediately relaxed. “Ah, no, he’s fine. That’s just my—ah—assistant, Monsanto.” He raised his voice. “Monsanto! Come over here. I’d like you to meet Dr. Smockwhitener.”

The man—Monsanto—peeked out from behind the easel. With a sigh, he set his pencil down and stood, walking around the easel and picking his way familiarly through the field of papery debris.

Monsanto peeked out from behind the easel.

As the man approached, Basil leaned over to Fergus. “Your assistant, is he? What kind of work are you doing, these days?”

Fergus shrugged. “Ah, well, you know, the family business. You could say—”

Monsanto arrived and bowed to Basil. “Good evening, Doctor,” he said, his voice pleasantly low. His hair was black and greasy, as if it hadn’t been washed in some time, and his eyes were darkly penetrating. His gaze was not a comfortable thing. “It is a pleasure to meet you. I have, of course, heard much about you.”

Basil shook Monsanto’s hand. It was limp, and damp, and Basil (following a handshake-evaluation protocol that dated back to ancient Mesopotamian presidential candidates) decided he didn’t much like the man. Still, he put on a smile. “It’s a pleasure, Monsanto. Fergus was just about to tell me what it is you do for him.”

The man inclined his head slightly. “I assist Mr. Curmudgeon in the meat processing facility.”

Basil raised an eyebrow in surprise and looked to Fergus. “Meat processing! Is that so? For some reason I thought the Curmudgeon business was dairy. My apologies for misremembering.”

Fergus shot a brief glare at Monsanto, but quickly looked back at Basil. “Ah, well, yes, the dairy business. That was a thing, too, years ago, but after my parents died and I took over, Monsanto and I made a few changes.”

Basil nodded. “Well, change is the one thing we can all count on, yes?” He chuckled. “Very good, very good. So, meat processing! Sounds fascinating. Where do you keep your livestock? The fields right around the castle seem to be been—ah—repurposed. What with the mazes and all.”

It was Monsanto’s turn to cast a glare at Fergus. “We had to move the herds,” he said, “some time ago. The smell, you know. It, ah, offended Her Ladyship.”

Basil raised another eyebrow at Fergus and extended a celebratory hand. “‘Her Ladyship’? I didn’t know you’d married, Fergus. Please accept my belated congratulations! Who is she?”

Fergus waved the handshake away. “It was a quiet thing. About five years ago, now. Hardly news.” He looked very uncomfortable. “Go on, Monsanto,” he said to his assistant, perhaps a bit sharply. “You can go back to what you were doing.”

Monsanto bowed and returned to his corner, where he resumed his apparent efforts at flooring the room in paper.

Once more, Basil cast about for something to talk about. He cleared his throat. “So, Fergus,” he said. “Those are some impressive mazes you’ve built out there.” He gestured in what he thought might be an outward direction.

Fergus nodded, but did not meet his gaze.

“Those were all fields before, as I recall,” Basil persisted. “Did you build them recently?”

Fergus shrugged uncomfortably. “Oh, five or six years ago,” he said. “I was hoping they would keep someone—ah, some people—out, but they weren’t too successful.”

Basil pursed his lips and nodded. He itched to ask for more details, but Fergus' reluctance was obvious. He took another tack, instead.

“The mazes really are well designed. How did you do it?”

For the first time, Fergus seemed to perk up. He lifted his head and glanced furtively at Basil. “You—you really think so? You really like them?”

Basil nodded sincerely. “Absolutely! Even aside from the physical construction, the layout is neatly conceived. I’ve got a bit of a soft spot for mazes; they’re quite fascinating.”

Fergus glanced about the room at the empty bookshelves. “Well, since you asked…” He got up and began rifling through piles of books, muttering to himself. “Where did that go? Haven’t looked at it in years, but I’m sure it’s around here somewhere…”

Basil watched in silence, a small smile hidden behind his bushy mustaches. He tapped the armrests of his chair absently.

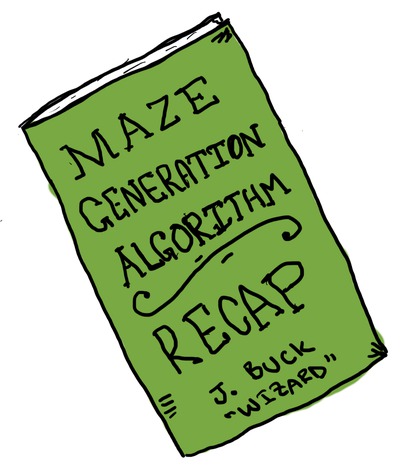

Eventually, after excavating more than half the piles in the room, Fergus held up a small book. “Eureka!” he shouted. He shuffled quickly back to his chair and sat down, breathing heavily as he showed the book to Basil.

It was a small book, more of a pamphlet, really. The title on the cover read “Maze Generation Algorithm Recap”.

It was a small book, more of a pamphlet.

“Oh,” Basil said levelly. “That one.”

Fergus looked astonished. “You don’t like it?”

Basil shrugged. “Oh, it’s all right, I guess, as far as it goes. It certainly gives a decent overview of maze algorithms. But the author—well.”

“The wizard, you mean?” Fergus asked. “What’s his name—Buck?”

“Oh, I’d hardly call him a wizard,” Basil scoffed. “More of a hack, really, but that little book of his is all right.”

Fergus narrowed his eyes a bit as he considered Basil, as if uncertain of what he was hearing. “‘Hack’?”

Basil shrugged again. “Anyway, my opinion here isn’t so important. Please, you were going to tell me how you designed your mazes!”

Fergus glanced suspiciously at Basil one more time, but went ahead and opened the small book. His movements were careful, gentle, running his hands across each page with obvious reverence.

“Well,” he said, clearing his throat. “I needed a maze quickly, so I first considered the binary tree algorithm—”

Basil tsked. “Oh, you almost never want that one.”

Fergus nodded eagerly. “Yes, I realized that right off. It definitely creates a maze quickly enough, but that diagonal bias it has is pretty severe.”

“‘Bias’?” Monsanto’s voice interrupted them from across the room. He was peeking around his easel.

Fergus glared, but Basil just nodded. “Yes, the algorithm’s bias. You can think of a bias as a kind of blemish that is common to mazes generated by that algorithm.”

Monsanto scooted around his easel, obviously intrigued, and blatantly ignoring his master’s glares. “So, like pimples or something?”

Basil smiled. “Sure, though I don’t know of any maze algorithms that incorporate pimples. Usually, biases are things like a preference for longer or shorter corridors, or a tendency for passages to move mostly in a given direction.”

“Ah!” Monsanto said, nodding, and leaned forward eagerly.

Basil continued. “Let’s say you take a maze generation algorithm and run it a few times, maybe create a dozen different mazes with it. If the algorithm generates truly random mazes, you won’t notice any blemishes—that is to say, biases—that are common to the entire set. Algorithms like Aldous-Broder and Wilson’s have this property—they generate what are called uniform spanning trees. But—ah—” Basil glanced at Fergus and saw the glowering look on the other man’s face. Clearing his throat, he shrugged apologetically. “We won’t go into that right now.”

Monsanto looked disappointed, but nodded again.

“But back to the binary tree algorithm,” Basil said. “It’s very simple—almost trivial, really—but it has a very obvious bias: its passages tend to run diagonally, as much as possible. In fact, if you start from the correct corner, you can reach the opposite corner without hardly trying, and without encountering any dead-ends!”

Monsanto was intrigued. “So why would you ever use that algorithm?”

Basil shrugged. “If you’re wanting a maze that can easily be extended, and where the path isn’t necessarily trying to run from one side to the other, it can be a quick solution. Say you’re designing some kind of treasure hunt, where the maze must be explored and not merely crossed. Also, with this algorithm you can generate an entire maze by considering only a single location at a time, independent of the rest of the maze. This can be handy in wizarding when your spells have a limited capacity—”

Fergus interrupted. “Regardless!” He held the book up and glared briefly at Monsanto. “The bias was precisely why I didn’t use that algorithm. I also considered the Sidewinder algorithm, but skipped it, too, for the same reason.”

Basil nodded. “Good choice. It’s a little better than the binary tree algorithm, but that vertical bias…” He shook his head.

“‘Vertical bias’?” Monsanto asked hopefully.

Fergus ignored him. “I was also intrigued by Eller’s algorithm, but the complexity wasn’t worth it for me. And it still had a bias on the final row, with that tendency to finish the maze with a single long corridor.”

Basil nodded sympathetically. “It’s an intriguing algorithm, but as you said, the complexity is something of a barrier.”

Fergus nodded as he flipped a few more pages in the book. “Then there was the randomized Kruskal’s algorithm, which looked pretty promising.”

Basil grinned and rubbed his hands together. “Oh! Kruskal’s. Yes, I’ve always thought that was an intriguing one, how it scatters little seeds all through the maze and builds them all up together. Though, I’ve never been partial to the way it tends to produce short, stubby passages. Always makes me think of porcupines, somehow.”

“Always makes me think of porcupines…”

Fergus tilted his head. “Well, yes, there is that. Randomized Prim’s algorithm has that same bias, actually. Ultimately, that’s why I discounted both of those.”

“What about the recursive division algorithm?” Basil asked. “I’ve always thought that one was clever, how it takes a large space and just subdivides it over and over.”

Fergus nodded eagerly. “Yes! I was really tempted to do that one, actually. Something about how it cuts the space in half with each pass kind of seemed appropriate to my situation at the time. But…the bottleneck bias was kind of a show-stopper for me.”

“Bottleneck?” Monsanto asked.

Basil glanced cautiously at Fergus, but for once he seemed not to mind the interruption. “The algorithm,” Basil said, gesturing, “works by cutting a space in half with a wall. It adds a single opening in that wall, and then repeats the process for each new space on either side, recursively. This produces corridors that act as bottlenecks for the solution—certain passages become obvious ‘choke points’ along the path. The solutions also tend to be short and direct—not very interesting, or challenging.”

Fergus shrugged. “Such a pity, too. I wanted that algorithm to work so desperately I even considered doing a hybrid algorithm, using a recursive backtracker or hunt-and-kill algorithm to work out a long, winding solution—taking advantage of the biases of those algorithms—and then filling in the rest with some variation on the recursive division algorithm. But I couldn’t quite make that work.”

Basil sighed appreciatively. “That’s clever! Hybrid algorithms are a fascinating lot. I think that’s why I’ve always loved the Growing Tree algorithm so much.”

“Me, too!” Fergus smiled—perhaps the first time Basil had seen him do so. It looked like he wasn’t very familiar with the exercise. “It’s actually the algorithm I settled on. I was fascinated by how I could change the biases of the generated mazes merely by making simple heuristic changes in the cell selection criteria!”

Monsanto shook his head. “You lost me.”

“What a surprise,” Fergus said, grinning viciously.

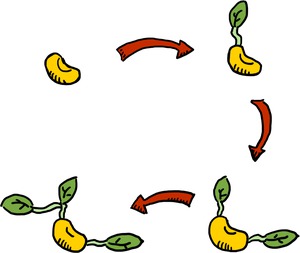

Basil leaned forward and looked between the two other men. “Now, now,” he said placatingly. “It’s really not so bad. Basically, the Growing Tree algorithm works by first planting a ‘seed’—the location from which you will start ‘growing’ your maze. We’ll put that starting location—that seed—into a list. It’ll be the only thing in the list at first, but each pass through the algorithm will grow the ‘tree’ a little bit by inspecting one of the locations in the list, selecting a new location right next to it, and then adding that new location to the list, too.

“The magic, though—” Basil smiled. “Ah, the magic happens in how you choose which element to inspect in the list. If you always choose the location that was most recently added to the list, you wind up with an algorithm that looks and acts very much like the recursive backtracker, with long, winding passages and relatively few dead-ends. If you always choose the location at random from the list, you get something much like a randomized Prim’s algorithm, with lots of short passages and an abundance of dead-ends. And—here’s the exciting part—if you sometimes choose the newest, and sometimes choose at random, you get a hybrid of both of those algorithms!”

Monsanto looked stunned. “That’s incredible! It’s like…like you’ve taken the essence of each algorithm, and spliced them together. Hmmm.” His eyes grew thoughtful.

Fergus nodded, his gaze suddenly concerned as he watched his assistant. “Anyway, it’s really useful, and pretty easy to implement, so that’s what I went with.”

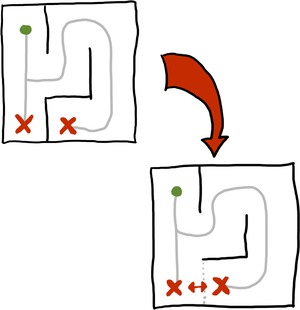

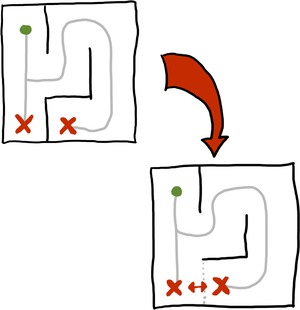

Basil stroked his mustaches thoughtfully. “I’m curious, Fergus,” he said. “The Growing Tree algorithm was an excellent choice, of course, but all of those algorithms you mentioned generate only perfect mazes. And I know, from looking at your inner maze, at least, that you’ve got a multiply-connected maze there.”

Predictably, Monsanto scrunched his forehead in confusion. “Multiply-connected?”

Basil nodded. “Right. A perfect maze—also called a simply-connected maze, has no loops in it. From a given point in such a maze, to any other point in the maze, there is only a single path. Not counting backtracking and the like, of course.”

“Ah!” Monsanto nodded. “So a multiply-connected maze has multiple paths between any two given points?”

“That’s right. You can also say it has ‘loops’ in it—you could walk in circles in such a maze.”

Fergus scowled at Basil and Monsanto. “If you’ll stop talking long enough for me to answer your question… Ready, now? Are you? Fine.

“Yes, my mazes are multiply-connected. It’s a simple process, really, to take a simply-connected maze and make it multiply-connected. You just find at least one dead-end, and then tunnel through it to a neighboring passage.”

“That’s all?” Monsanto asked.

“That’s all,” Fergus said. “You can show it works because of what we said about perfect mazes. If there is only one path from where I am, to the dead-end, and only one path from where I am, to that point in the neighboring passage, then if I tunnel through from the dead-end to that neighboring passage, suddenly I have two paths to the dead-end—the original one, and now the one through that neighboring passage. Voilà. A multiply-connected maze.”

Basil nodded approvingly. “Very clever. You could even take that to the extreme and do that to every dead-end in the maze.”

“I considered it,” Fergus said. “But I don’t like the aesthetic of braid mazes. I know they can be challenging, but I like the effect of dead-ends on morale.”

“Braid mazes?” Monsanto asked. “Is that what you call a maze with no dead-ends at all?”

Basil nodded. “That’s right.”

Fergus closed the little book and set it aside. “Once I knew the algorithm I wanted, it was just a matter of summoning a Walker to pace out the passages, and then quick-growing hedges to form the walls. Took about three days, all together.”

Basil nodded, eyes twinkling over his voluminous mustaches. “Well, very nicely done, Fergus. The Conclave would be impressed! These really are extraordinary mazes. The height of the hedges is particularly intimidating.”

Fergus seemed to appreciate the praise for a moment, but then dropped his gaze to the floor again, glowering. “Well, little good they did me. They failed to keep someone out, and they failed to keep someone in. At this point, they only earn me complaints from the Imperial Courier Service.”

Basil sighed as a brooding silence descended on the room again. Even Monsanto scooted back behind his easel and resumed his curious efforts with pencil and paper. Fergus seemed to be dwelling on dark thoughts, his face set in a scowl so poisonous it threatened to take the polish off the table between them.

Basil knew he had to make another effort on his manservant’s behalf. He cleared his throat carefully. “Fergus, I know you don’t want to discuss it, but I really must insist. If I promised to take Fabian away with me, and not return, would you be willing to remand him into my custody?”

Fergus hesitated, but then shook his head. “No,” he said gruffly. “He has too much to answer for.”

“What did he do?” Basil asked gently. “What is he guilty of?”

Fergus shook his head. “Meddling,” he said. “And that’s all I’ll say on the matter.” He looked at Basil, his gaze troubled. “I’ll summon a servant to show you to your room.”

Basil sighed, but nodded. “Thank you, Fergus.”

The two men got up and walked to the door, where Fergus pulled on a tasselled rope that hung beside it. Nothing seemed to happen, but a few moments later the door opened and a young man quietly peeked in. “Yes, sir?” he said softly. “You rang?”

Fergus told the young man to guide their guest to the room that had been assigned to him. “Supper is at seven,” he added, speaking to Basil. “We’ll dine in the great hall. He can show you the way, if you like.” He gestured to the servant.

Basil thanked Fergus again, and then followed the young man out into the damp hallways. How, he wondered, was he ever going to get Fabian out of this one?